A soldier’s daughter reminds us that children are often the forgotten casualties of war and the line between one’s friends and enemies is not always so clear.

**WARNING. This article contains images and references to war and violence, which some may find distressing and/or triggering.**

Story and Photos by Donna Musil

When I was sixteen, my father died from cancer.

Today, it would be presumed to be related to Agent Orange, the deadly defoliant the U.S. dropped on Vietnam during the war, exposing millions of friends and foe alike. When he died, my father and I weren’t on the greatest terms. He was an authoritative military man in the Vietnam War and I was an obstinate teenager. Toss onto that simmering stack of charcoal raging adolescent hormones, 11 moves in 15 years on three continents, and the fear of losing a parent — well, you can imagine the flames on that particular fire.

It wasn’t always that way.

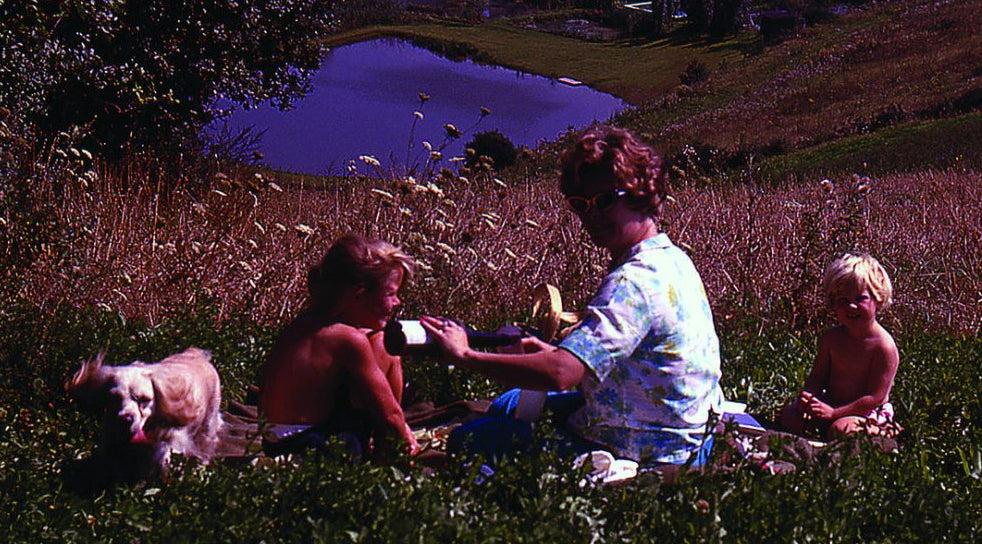

Lieutenant Colonel Louis “Bud” Musil was a hands-on kind of dad. He was up at five a.m. cooking chicken gizzards (for the extra protein) before my swim meets in San Francisco. He made sure our cocker spaniel, Penny, flew across the Atlantic Ocean with us, no matter the cost. And he and my mother dragged our tiny, whining bodies to every temple, museum and monument across Europe and Southeast Asia, including the World War II concentration camp memorial in Dachau, Germany, when I was 10.

Because Bud Musil was no “ugly American.” He wanted to make sure we saw the good, the bad and the ugly in the world, the causes and consequences of war, not just the platitudes. He joined every cross-cultural friendship group he could find. To this day, my heart skips a beat every time I pass an airport, and I detest nationalism. Cultural preservation is one thing – but there’s a very thin line between patriotism and xenophobia.

When I was 7, my father went to Vietnam for a year.

He was a military lawyer assigned to a combat unit with the 173rd Airborne Brigade “Sky Soldiers” during some of the war’s bloodiest battles. He slept on a cot in a tent that also served as their legal office and courtroom. His duties ranged from investigating U.S. war crimes to managing the debts of soldiers struggling to stay alive in the North Vietnamese Army (NVA)- covered hills of the Central Highlands.

In 10 months, he tried 103 courts-martial and reviewed 942 Article Fifteens (nonjudicial punishments for disciplinary action), then focused on rehabilitating the convicted, saving many a military career.

Apparently, he did a decent job. In a recommendation for a Bronze Star, an eyewitness claimed Bud Musil’s approach “was marked by a maturity, wisdom, fairness, and understanding of human nature in a degree rarely found in individuals of his age and experience.” The eyewitness said he had an “intense interest in judiciously safeguarding both [the] rights of the individual and the interests of the United States Government” and was truly a “soldier’s advocate.”

VIEWING THE VIETNAM WAR FROM THE OTHER SIDE

In January 2019, my husband and I took a trip to north and central Vietnam. I hesitate to call it a vacation. We did a few touristy things: took an intimate cruise on a junket ship in Halong Bay, saw a traditional water puppet show in Yen Doc village, and shopped ‘til we dropped amongst the balustrades and bougainvillea of Hoi An. But we also wanted to explore the more tragic and bittersweet aspects of what the Vietnamese call the “American War.”

We weren’t naïve about military conflict. My mother-in-law was a pretty blonde, blue-eyed teenager when the Russians and Mongols invaded Berlin at the end of World War II and raped thousands of pretty blonde, blue-eyed teenagers. My father’s best friend died in Vietnam, and after the war, I watched him drink himself to sleep every night with a good book and a better gin and tonic.

I had also spent 20 years documenting the emotional and psychological influences of trauma and war on military children and families, so my husband and I knew the consequences of war, one step removed.

What we didn’t know could fill an encyclopedia.

We started at the Ho Chi Minh memorial in Hanoi. I didn’t know much about Ho Chi Minh at the time, the Vietnamese revolutionary and first President of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. But as we toured his austere home and read about his travels to France and admiration for America’s founding fathers, I couldn’t help but note the irony of America backing the South Vietnamese capitalist republic instead of the North Vietnamese communist republic who fought for and won their country’s independence from the French and Japanese, as the U.S. had done from the British.

As we entered the mausoleum in a hushed, straight line, I was surprised to see the embalmed body of Ho Chi Minh lying there, as if he could wake up any moment and invite us for tea.

Maintaining this perception takes a lot of work, apparently. For the last six years of the war, his body was hidden in a cave and still must be transported to Russia every year for two to three months of maintenance. Ho Chi Minh specifically asked to be cremated in his will. He lived a modest life and wanted his ashes buried in three simple urns in the hills of northern, central, and southern Vietnam. Instead, his mummified body lies inside a glass casket, where thousands of visitors and devotees come to pay their respects.

THE HANOI HILTON

Our next stop was Hoa Lo Prison, often referred to as the “Hanoi Hilton,” where U.S. Senator John McCain was held captive for five years after crashing into downtown Hanoi’s Truc Bach Lake during a bombing run. Built by the French, the prison also housed scores of Vietnamese who fought for and eventually won their independence at Dien Bien Phu. As our young guide led us through the dark, dank cells, I recalled similar heartbreaking tales of brutality and brotherhood at the National Infantry Museum in Columbus, Ga., U.S.A., the memorial at Dachau, and in countless other museums around the world.

I suppose that’s what John McCain was doing when he tried to normalize relations between the United States and Vietnam in more than two dozen visits following his release. When McCain died in 2018, hundreds of Vietnamese well-wishers left flowers and incense at the Hanoi monument that marks his capture. I don’t think anyone “forgave” each other, or forgot the cruelty and carnage inherent in every conflict, but I guess they decided to make the best of a bad situation and focus on the future they faced, if not the one for which they had fought.

DAK TO: THE BLOODY BATTLE

We continued our journey in Pleiku, the capital of the Gia Lai Province, in the heart of Vietnam. Our guide, Cham, was a Montagnard, one of the indigenous “people of the mountain” of the Central Highlands. His face was weathered, but his smile was kind and his eyes astute. For twelve hours, he shared what he could through dusty backroads, shrouded waterfalls and rows of rubber trees tourists rarely see. It was magical. It was also emotionally grueling. Our primary destination was an abandoned airstrip in Dak To (or Dac To), near the Cambodia/Laos border.

Filmmaker Ken Burns dedicated an entire episode to the battles of Dak To in his television series “The Vietnam War.” My father had arrived in Oct. 1967, a month after the NVA leadership decided to lure U.S. forces into the rolling hills and “crush” them, according to “Military Operations in the Central Highlands,” a memoir I picked up at Hoa Lo Prison.

It was written by the Chief Commander of the operation, Hoang Minh Thao, who helped build the Vietnam People’s Army. The book was hard to read. I had to keep reminding myself that we had been the “enemy,” and the dead were my father’s friends and brothers-in-arms.

Despite the combined efforts of the 4th Infantry, 1st Cavalry, South Vietnamese ARVN, and 173rd Airborne Brigade, which Thao called “one of the crack units of the U. S. Expeditionary Corps,” the Viet Cong were able to parlay lessons from previous battles with the U.S. at Ia Drang and the like into seventeen days and nights of continuous battle, “crippling” the U.S. forces, particularly the 173rd, by killing 344 soldiers, wounding 1,441 more and shooting down 38 planes and helicopters.

The battle also included relentless attacks on the Dak To airfield and Tan Canh military base in a “most horrible firestorm” that destroyed two C130 planes, seventeen thousand gallons of fuel, and thirteen hundred tons of ammunition. An officer with the 173rd called it a “bloodbath.”I don’t know who that officer was, but as I stood on the same airfield, I tried to imagine the fear my father must have felt as the bombs exploded around him.

In one of his legal files, I recalled a casual remark he made about dragging bodies off a hill and photographs of mutilated Viet Cong soldiers. I watched an old woman pick through the rubble at the end of the runway that morning; for what, I couldn’t tell. Our guide told us the runway is used to dry cassava now, a starchy tree root that locals eat.

We considered, but couldn’t venture into the hills where the hand-to-hand battles were fought, because bombs and booby-traps were still hidden amongst the foliage.

As we drove away, our guide shared his own war stories. He said he was a young man at the height of the conflict, studying at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. He had received a full scholarship from a Christian organization he met by chance while studying in Saigon, now Ho Chi Minh City. Upon his return, after the NVA won the war, he was sent to a “re-education camp” (nee prison) for two years, presumably for attending the Western institution.

For three of those months, he sat alone in complete darkness. He was lucky; his cellmate and many others were beaten and executed.

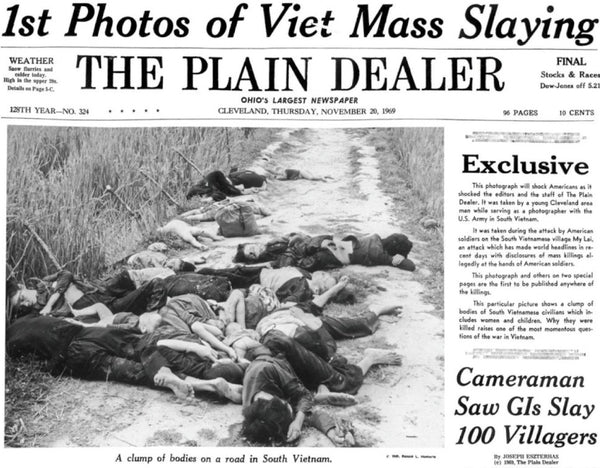

MY LAI MASSACRE

Two days later, our other guide, "Ken," told us he also spent time in a re-education camp after working as a translator during the war. He was still translating when he took us to the Son My Memorial, honoring the victims of one of the worst civilian casualties of the war. On March 16, 1968, American soldiers massacred more than 500 unarmed elderly men, women, and children in a small village called My Lai and its surrounding areas. I had wanted to visit the memorial for years.

My father was in Vietnam during the same time period, and the soldier who led the slaughter, Lt. William Calley, once ran a popular jewelry store in the town where my mother lives. I had watched Calley eat a chili dog one day at a local delicatessen, three tables over from me. I had wanted to say something but was too scared, so I sat there frozen, pretending he was just another customer.

Calley was a diminutive man at 5’4,” who reportedly led a non-descript life after the massacre. But on that particular day in Vietnam, he and his “brothers-in-arms” shot, stabbed, beat, blew up and mutilated 182 women (including 17 pregnant women), 173 children (including 56 babies under five-months-old), 60 villagers over sixty-years-old and 89 middle-aged villagers, wiping out generations of families for decades to come.

Pham Thanh Cong was 11 years old when the U.S. invaded My Lai at daybreak. Like most families, he writes in his memoir, “The Witness from Pinkville,” he was eating breakfast with his mother and three sisters, one barely two years old. Other boys were already working in the fields with their grandfathers.

Suddenly, a shower of missiles and bullets began raining down on their heads, as nine helicopters hovered, firing rockets and machine guns. The farmers and field boys were the first to die. Then houses, food, and livestock were burned to the ground. Mothers wailed while their daughters were raped and sodomized.

Pham Thanh Cong and his family hid in an underground dugout until three soldiers arrived and forced them out. They set their house on fire and killed their buffaloes. Then the soldiers huddled together, mulled something over, and forced the family back into the dugout.

Just as his mother realized what was happening, one of the soldiers tossed in a grenade, killing everyone but the boy. Afterward, Lieutenant Calley and his troops marched 170 residents of the tiny hamlet to an irrigation ditch and methodically mowed down “anything that moved.” When a baby tried to crawl out from under its dead mother, Calley tossed the child back on the heap and shot it dead.

Not every U.S. soldier followed Calley’s orders. One-shot himself in the leg to avoid participating. Helicopter pilot and Military B.R.A.T. Hugh Thompson, along with his crew chief Glenn Androetta and gunner Lawrence Colburn, rescued a dozen civilians that day, after warning Calley he was committing a war crime.

Calley told Thompson to mind his own business, stating, “this is my show. I’m in charge here.”

Thompson and his crew took off, angrily, refueled and returned, pulling one girl out of a ditch and landing their plane between ten villagers running from other soldiers.

Thompson told Colburn and Andreotta to shoot the U.S. soldiers if they tried to stop the rescue. For a year, the mass slaughter was covered up by the United States military, until it was finally exposed through the dedication, conscience and courage of helicopter gunner Ron Ridenhour, combat photographer Ronald Haeberle, journalist Seymour Hersh, and Thompson’s crew. I’ve often wondered if my father knew about the massacre, and if so, what he thought or did (if anything). I know he prosecuted American soldiers for war crimes, but he wasn’t attached to Calley’s platoon as far as I know.

THE COST OF WAR

The story fueled the U.S. anti-war movement. Others made excuses for the inexcusable. It was the “cost of war,” some shrugged. They were “avenging” their fallen friends.

None of this was true. Calley had barely been “in-country” and had experienced little direct combat.

Pham Thanh Cong, meanwhile, was struggling to survive without his mother and siblings. His father helped as much as he could while serving as the Security Commissioner and Chief of a separate village.

In 1969, Calley was charged with multiple counts of premeditated murder, along with others. Only Calley was convicted, but he served just three years of house arrest in Columbus, Ga. before Judge Robert Elliott released him. President Richard Nixon pardoned him in 1974. Then-Governor Jimmy Carter told his fellow Georgians to “honor the flag” as Calley had done and leave their headlights on to show their support.

A few months after Calley was charged, twelve-year-old Pham Thanh Cong’s father was killed in a U.S. raid on the Son Quang commune. Some of his last words were to please help his son, “He has no more family members to rely on.” After he was released, Calley spent the bulk of his life selling jewelry in Columbus, then moved to a gated luxury apartment complex in Fla., and finally, Atlanta. He apologized in 2009 — but not really — he still claimed he was “following orders.”

Apparently, Calley missed the lesson about the Nuremberg Trials after World War II. The day my husband and I visited the My Lai/Son My Memorial, the museum was empty, save a class of Korean university students speaking with two of the massacre’s survivors — Pham Thanh Cong and Mrs. Pham Thi Thuan (not related) – about similar atrocities inflicted upon the Vietnamese by the Koreans. We were allowed to observe, then Cong agreed to speak with me personally.

He was retired now, but he had developed and managed the memorial for many years. Despite the melancholy nature of our conversation, Cong immediately put us at ease. I asked whether he thought war brings out the worst in people or allows bad actors to do terrible things.

Like the students, I wondered how he and his fellow survivors coped emotionally with such trauma and loss.

The hurt they bear is unhealable, he assured me. He still has nightmares, 50 years later. It is a pain that all war victims share, he said. Yet, he is acutely aware that moving forward is the only way for him, personally, and his country to forge a better future. They don’t teach Vietnamese children about My Lai in school, he told us, but 40,000 people visit the memorial each year from 80 countries.

His own family is growing, as well. He and his wife have three children, who are now bearing children of their own.

SAYING GOODBYE

Two months after my father’s cancer was discovered on my sixteenth birthday in 1976, I was riding around Fort Knox on my bicycle, heading nowhere in particular. I decided to stop at the Ireland Army Hospital, an offwhite, multi-story behemoth that resembled a Soviet housing block. He was in a coma at this point and my mother and grandmother took turns manning his bedside, holding his emaciated hand.

I didn’t like going to the hospital. I was still angry at my father — for being so controlling, for moving me away from my San Francisco swim team, for dying. But I leaned my bicycle against the building behind a bush and hoped it would be there when I returned.

I was surprised when I opened the door to his room and neither my mother nor my grandmother was there. It was just my father and me alone, while the air conditioner hummed softly in the background.

He looked like one of those concentration camp victims we had seen in Dachau. He couldn’t have weighed more than 85 pounds. I leaned against the bed rail for a moment in silence, then told him I was sorry — for being such a jerk and arguing every night at the dinner table.

He breathed out of his mouth in tandem with the air conditioner. I told him I was sorry for sneaking off to parties in the middle of the night and for screaming, “I wish you were dead!” when he punished me afterward, as any good parent would do. He didn’t answer, of course. He was in a coma. But when I started to cry and asked him to forgive me, I swear he nodded, just a little. I don’t know if he really did or if I just imagined it. They say a person’s hearing is the last thing to go, but who really knows? I hope it’s true.

My father died that night, at 42 years old. Like Pham Thanh Cong, I had lost the one man in the world who truly loved and understood me. The Vietnam War had taken both of our fathers, and his mother and sisters. We would never be the same and neither would our countries, but at least I got to say goodbye, which is more than I can say for many.

“The wheel of history goes on and on,” Pham Thanh Cong says at the end of his book. If only someday, it would roll in the direction of peace.

Leave a comment

All comments are moderated before being published.

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.