By Paulette Bethel

When I was 7 years old, I went for an extended visit with my treasured great-grandmother. Always a highpoint of summer vacations, I indelibly remember the excitement of being invited to attend mass with one of my favorite great uncles and his daughters.

Upon arrival, we settled into the pews near the back of what I now know was a segregated Catholic church. I was happily seated between he and my older cousins, feeling secure and loved. I still vividly remember my wonderment at observing my very gentle and elegant uncle carefully remove his fedora from his head and gingerly placing it next to him.

I followed his example by removing my white lace head covering. My older cousins began to chuckle in amusement, as he quickly replaced it (at that time, it was the catholic custom for females to keep their heads covered). These are the things that build wonderfully, enjoyable childhood memories.

That same morning, I also remember a strange woman walking quickly toward us in a way that I could see concerned my uncle. Without addressing or acknowledging my uncle, she pushed her body passed him and attempted to remove me from his care. Fearful, I pulled back and buried my face against his body for protection. She responded by pulling on me even harder and saying:

“Honey, you need to come with me. You are in the wrong part of the church. You belong in the front with the white people.”

Pulling me out, she quickly ferried me to the front of the church.

RUN BABY, RUN

After being reseated and feeling scared, bewildered and having no idea why she had removed me, I immediately got up and ran to the back of the church screaming, “I want my uncle!” To this day, I can see the hauntingly silent and stoned look on my uncle’s face, as I crawled back to safety, sitting next to him. When we finally reached the car after mass ended, my cousins humorously (protective coping mechanism) explained what had transpired: It was due to my racially mixed background and ambiguous appearance.

Though this story eventually became a lighthearted legend within my family, I never once heard my uncle speak of it. At the tender age of seven, and before I even learned the language to name it, I had experienced the painful reality of racism. Though young when my story occurred, 60 years later I still recall it as if it happened yesterday.

RACISM, COLORISM AND HISTORY

This early Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) encounter exposed and hurled me into the ugly sheets of racism, colorism and a history rooted in the vestiges of slavery in the Americas. I suspect that the silence I witnessed with my beloved uncle was a strong survival response, in reaction to behaviors frozen in the history and the iniquities of white supremacy, or what Ta Nehisi Coates describes as a visceral experience, that dislodges brains, blocks airways, rips muscle, extracts organs, cracks bones, breaks teeth…

THE EFFECTS OF GENERATIONAL TRAUMA

“Lost in Transmission: Studies of Trauma Across Generations,” a compilation of essays edited by M. Gerard Fromm, sums it up this way: “The effects in African descended communities, trauma is passed down like an inheritance. What human beings cannot contain of their experience — what has been traumatically overwhelming, unbearable, unthinkable — falls out of social discourse, but very often onto and into the next generation as an affective sensitivity or a chaotic urgency.”

According to psychiatrist Dekel Goldblatt, transgenerational trauma, or intergenerational trauma, is a psychological term which asserts that trauma can be transferred between generations. This theory posits that after the first generation of survivors experiences trauma, they can transfer the trauma to their children and further generations of offspring via complex post-traumatic stress disorder mechanisms. Some researchers refer to this as Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome (PTSS).

The reaction to people in the African diaspora stems from the violence that led to the traumatizing conditions perpetrated against black people during the transatlantic slave trade and inheritance of trauma from 400 years of enslavement that persists. It continues to pass down its effects and the impact of new trauma, generation to generation and, according to epigenetic researchers, can be passed on through our DNA.

INTERGENERATIONAL TRAUMA

Accordingly, this passing of trauma can be rooted in the family unit itself, or found in society via current discrimination and oppression. The traumatic event does not need to be individually experienced by all members of a family — lasting effects can remain and impact descendants from external factors. For example, black children’s internalization of others’ reactions to their skin color manifests as a form of lasting trauma originally experienced by their ancestors.

“I witnessed the trauma of the generation before me,” say generations of the author’s family.

Yukon comedian Sharon Shorty says: “As I reflect upon my personal story and complex family legacy, rooted in the deep emotional woods of slavery and a history that includes slaves as ancestors and being the descendant of plantation owners, both through the legitimacy of marriage and forced sexual alliances. I hear the drumbeat of generations of my African ancestors existing through the brutality of bondage, rape, torture and the Code Noir Laws of my native Louisiana.”

When hearing our family legend of my runaway female slave ancestor, who is said to have run through alligator-infested swampland to get to safety and her freedom, she speaks to the horrors of slavery within my own family.

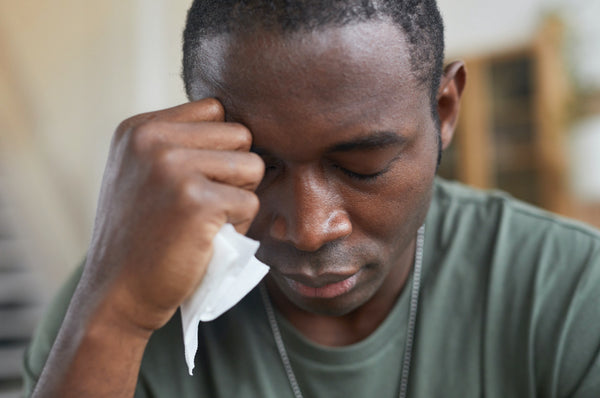

Providing an inheritance and heritage of strength carried on her shoulders through struggles that I have encountered to this day—considering the recent activities involving Amy Cooper and her reprehensible threats of police involvement against Chris Cooper (no relation) in New York’s Central Park. Coupled with the brutal killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Abery, I find myself once again faced with trying to make sense of this unspeakable pain and racialized trauma.

The footage of George Floyd’s murder reopened too many familiar wounds of racial injustice, racial profiling of my husband and sons, systemic and structural racism, white privilege and white supremacy that carries with it the traumatic pain of decades of suffering and unresolved grief at the deepest level of my broken spirit. Like many black Americans, the trauma from these grotesque murders serves as a blatant reminder of generations of great violence that is too often perpetrated upon black and brown bodies.

A LASTING LEGACY

Whether described as multigenerational trauma, transgenerational trauma. Intergenerational trauma (PTSS) or historical trauma, there is a growing body of literature that addresses the historical significance of the black experience in the inheritance of the legacy of enslavement. It recognizes, what one our most famous Third Culture Kids (TCKs) and president, Barack Obama says is “the long history slavery and Jim Crow and redlining, institutionalized racism that has too often been the plague or the general sin of our society.“It’s a flowing river of connection – an emotional collector of all of the pain from oppression,” says Bobbie L. Parish, CTRC-S, Executive Director of the International Association of Trauma.

Like me, many people in the African diaspora still viscerally hear the drumbeat stemming from the carried intergenerational trauma and complex family dynamics rooted in the dark legacy of slavery. The 2018 documentary “Unchained: Generational Trauma and Healing,” examines the lingering trauma handed down from the American slavery system, men and women were interviewed about the steps they have taken to break the emotional chains passed down from their slave ancestors.

The ability to break these chains of intergenerational bondage requires the audacity and moral courage needed to tackle trauma rooted in historical, institutional and structural racism. Enhancing understanding on the impacts of the transfer of trauma between generations may lead to the healing of unresolved grief and the ability to discover useful posttraumatic survival strategies that lead to the development of Post-Traumatic Growth (PTG) and may potentially offer a lasting resolution to minimize the negative aspects of past and future intergenerational transmission of ancestral trauma.

-----------

PAULETTE BETHEL, PHD is a career U.S. Air Force officer, trauma recovery coach, global transition expert and a mother to Third Culture Kids. Culturally and racially blended, Dr. Bethel is our expert on the importance of transition and its effect on relationships. She is CEO and Founder of Discoveries Coaching & Consulting.

Leave a comment

All comments are moderated before being published.

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.